a manifesto-meditation on the life of all things

amilton de azevedo writes about Nigamon/Tunai, by Émilie Monnet (Anishinaabe/Canada) and Waira Nina (Inga/Colombia), presented in the 2024 Festival TransAmériques (FTA – Tiohtià:ké/Montreal). this text is part of a special coverage; the critic traveled to Canada at the invitation of the FTA.

For a long time, we have been alienated from the organism to which we belong — the earth. So much so that we began to think of Earth and Humanity as two separate entities. I can’t see anything on Earth that is not Earth. Everything I can think of is a part of nature. (Ailton Krenak – Ideas to Postpone the End of the World)

Way before a part of a continent was called South America, Indigenous populations from various regions, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, passing through the Andes Mountains, were able to maintain cultural exchange and trading goods. The Peabiru Trail (in tupi, “pe” means path and “abiru”, crushed grass) connected the current southeast Brazilian coast city of Sao Vicente to Cusco, in Peru, besides other branches linking other places. Nigamon/Tunai (Canada, 2024), by Émilie Monnet and Waira Nina, seems to operate towards the creation of their own bridges; their yaku ñan, as if the waters from Amazon rivers could run within the Great Lakes’ and two Indigenous realities would be entangled. And being nature oneness, why wouldn’t they?

Monnet, of French and Anishinaabe (First Nations) origin, and Nina, from Inga Nation, chooses water and copper as the main matters and the sound as the main form: Nigamon/Tunai are, respectively, the Anishinaabemowin and Inga language for song. Through the natural forces – water, wind, gravity – they activate a living installation that connects North and South, integrating the audience, the artists and the trees and everything within the space of Théâtre Espace Go in a performance that establishes itself as a manifesto-meditation on the life of all things.

- Read more: access this link for more theater critics written in english

- Read more: follow ruína acesa’s FTA special coverage

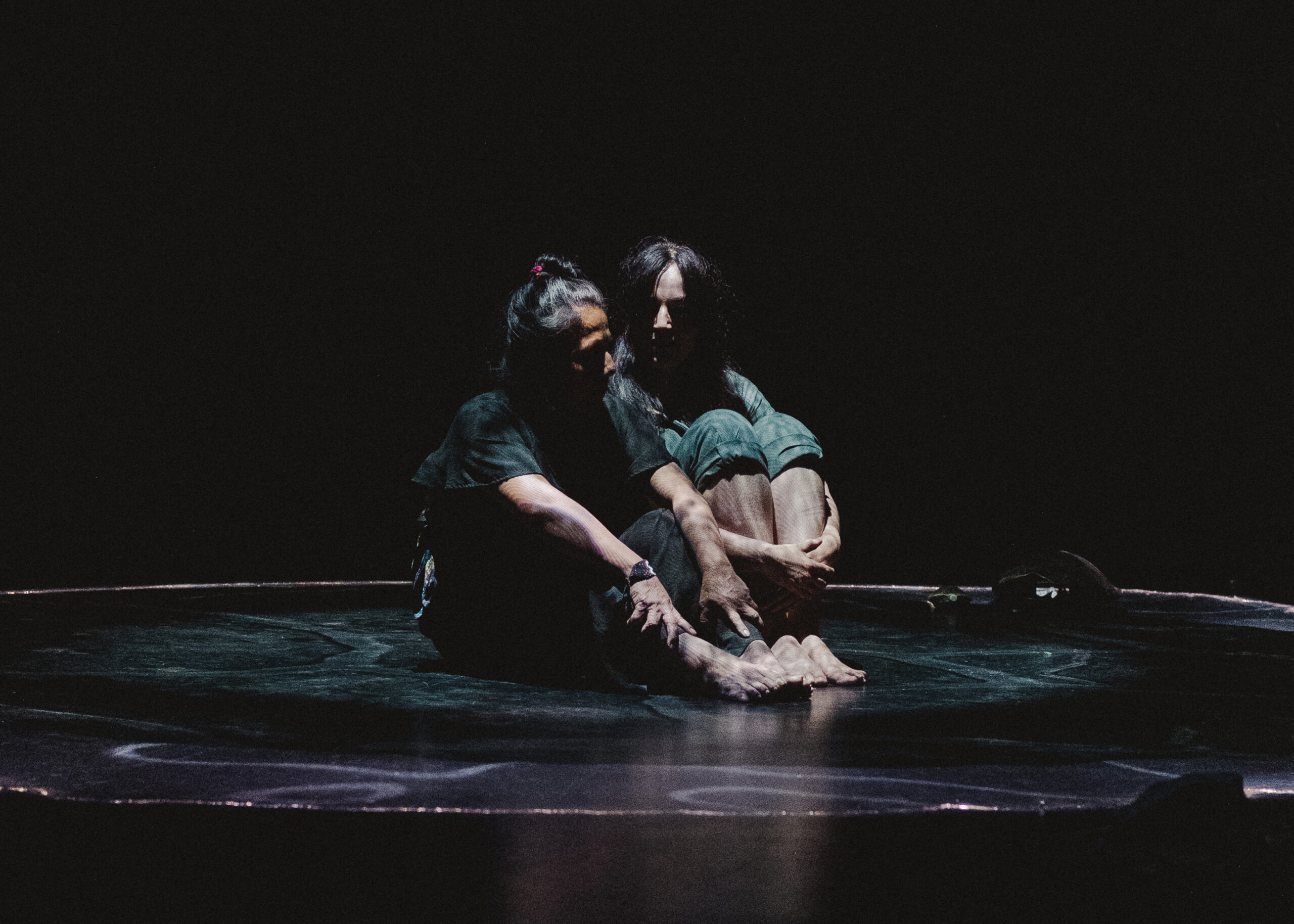

Nigamon/Tunai starts with a blessing. Copper hoops in motion by the hands of Monnet and Nina sings to the air passing through them. They walk around the space, approaching the audience with the bright sound and crowning some of the people. At the beginning, many viewers were still engaged in conversations, taking some time to realize that the performance had already begun – and it probably began even before, way before, the public went into the room.

It is quite a challenge to translate organic experiences into aesthetic expressions. The forest – being it amazonian or boreal – infinite forms of communication present themselves in the daily lives of Indigenous populations that are able to remain in their territories, their lands. Monnet and Nina summoning birds chants can be a funny moment, but one must reflect upon the risk of the laughter being brought upon by an exoticist attitude. As Brazilian Indigenous leader, environmentalist, philosopher and writer Ailton Krenak wrote in his Ideas to Postpone the End of the World,

“my communion with what we call nature is an experience long scoffed at by city folk. Rather than see any value in it, they poke fun at it: ‘He talks to trees, he’s a tree-hugger; he talks to rivers, he contemplates the mountains.’ But that’s my experience of life. I don’t see anything out there that is not nature.”

In order to make this wholeness perception emerge for the audience, the performance organizes itself in a kind of Indigenousfuturist perspective. For what it was, for what it should be: Nigamon/Tunai materiality is an entanglement of contemporary and ancestral technologies. There are the natural elements, a traditional drum, a turtle shell, the chants, the trees. There also are the intrique sound design by Leonel Vasquez, the psychedelic projections on the video designed by Mélanie O’bomsawin and the living light by Chantal Labonté. South and North, past and present, coexisting as one towards an integrated future.

Their approximation between originary populations of Abya Yala and the First Nations does not intend to simplify complex and singular cultures, but to understand that they both are guardians of their lands and struggle against quite the same enemy. The mechanisms of globalist capitalism can reach every edge of the world, and what has always been destroying nature – killing rivers, mountains, forests, populations, the future – is colonization and extractivism.

The at some extent immersive installation invites the audience to take part in a world building action based on both Anishinaabe and Inga nations cosmovisions, especially from their mythical relation with the turtle and their waters. Nigamon/Tunai is a microcosmos on its own, but it doesn’t let the whole nature under attack outside. A world is built and a world is burnt as trees light up and one can hear chants in different languages whilst feeling their stems and leaves; and one can also hear the symphony of destruction and the forest becoming a cemetery. But when you bury a seed, it regrows. And everything vibrates and there is still life.

The misé-en-scene itself is the forest and its mysteries; depending on where you sit, some scenes will be more or less seeable – in nature, you have to open your eyes, ears, heart and soul to realize the invisible life that lies on all things. Nigamon/Tunai can also be experienced as a cleansing performance, sharing this healing force with the copper, metal used to build the instruments and the reason that Inga lands are at risk. They use the copper that is on the surface, as it is a gift from mother earth; extractivism digs it up from giant holes that make mountains disappear. Capitalism does not listen to nature. Nigamon/Tunai invites the audience to literally hear a rock. They say much.

Uma crítica gigante!

Un manifiesto