to fall and to be held (and to whatsoever else)

amilton de azevedo writes about Multitud, by Tamara Cubas (Uruguay), presented in the 2024 Festival TransAmériques (FTA – Tiohtià:ké/Montreal). this text is part of a special coverage; the critic traveled to Canada at the invitation of the FTA.

When nonlocality guides our imaging of the universe, difference is not a manifestation of an unresolvable estrangement, but the expression of an elementary entanglement. That is, when the social reflects The Entangled World, sociality becomes neither the cause nor the effect of relations involving separate existants, but the uncertain condition under which everything that exists is a singular expression of each and every actual-virtual other existant. (Denise Ferreira da Silva – On difference without separability)

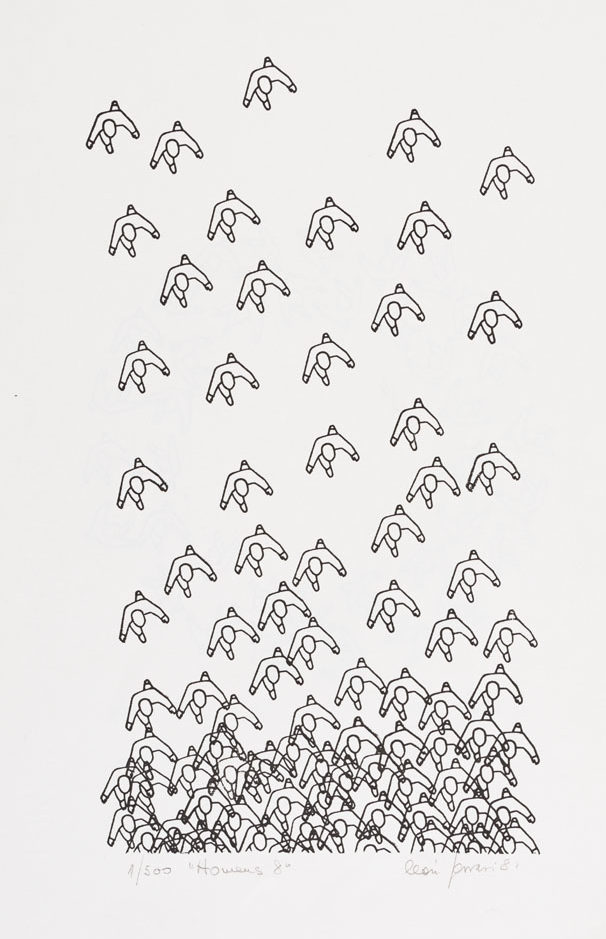

To fall. A verb, a gesture, an action, a choice, a failure. One hundred performers take their places on the open-air stage. Multitud (Uruguay, 2014) begins with some sort of order; building cosmos just to turn it into chaos. They start to tremble and to fall. One action, infinite possibilities within it. Different speeds, trajectories, angles and ways to descend from standing to lying on the floor. The original music by Francisco Lapetina and Martin Craciun, a massive soundscape, builds up the atmosphere and provides subtle (and not-so-subtle) cues for the transformations in movement and attitudes.

Tamara Cubas’ choreographic composition throughout the work makes a hundred people organize themselves as a chorus, a crowd, a rabble, a pack and something else. To exist collectively is not a simple equation and Multitud multiple configurations not only is aware of that but its trajectory seems to aim exactly at such complexity. The structure of the work appears to be open for one to follow, in the sense that the mechanisms and apparatus that sustains the actions performed are somewhat visible, especially at its beginning.

- Read more: access this link for more theater critics written in english

Multitud is, among many things, a true masterclass on composition. The tools utilized by Cubas are recognizable from theater practice and classes, like common exercises and Viewpoints methodology; their use, both considering the rehearsal processes and the artistical result, is quite effective within its context. Daily configurations, people crossing themselves on the street, our society organized through movement – and through not looking to one another; to pass by, to ignore, to not recognize thy other. But Cubas makes an investment in how to shape time in order to rearrange the audience’s glance upon what is going on. Some sort of calmness is perceived in each scene build-up, as if in stretching time the multitude watching can, as said by Bertolt Brecht, “distrust the more trivial, in appearance simple. And examine, above all, what seems habitual“.

As if the common day dynamics, somewhat overlooked by people in their regular lives, in a both precise and chaotic arrangement on stage, can be strange; as if revealing the structure is a way to rip the structure to its roots. Later on, the opposite can happen: as the scenes develop at their own pace, a firstly strange image can be normalized until it becomes something else in the audience’s multitudinous mind.

That mirroring – or confrontation – between Multitud and the multitude of watchers is another aspect to consider. During the May 23rd presentation at the Place des Festivals for the FTA (Montreal/Canada), when performers were running on stage, a group of young girls stood up to leave; and they did it running, perhaps not even aware that for that brief moment they became a part of the artwork. People would talk during the performance, two friends took a selfie of them whilst “watching”, and so the ideas and configurations of a coexistence are not only seen at the composition proposed by Cubas, but also in the spontaneous (and sometimes chaotic and even unpleasant) composition performed by the audience watching.

In the open space, Multitud becomes part of the city where it is presented. To stay present and focused is not a simple task considering everything that it involves – people could be leaving because of the cold weather, but also because of the progression of the show, and one could never say for sure what makes one stay and what makes one leave. There is, though, the feeling that Multitud is not designed to be seen in an arena, from all the sides; some of the most high-voltage images presented are thought within the context of a frontality, being one side of the audience privileged in that sense.

And the multitude in the audience, as an innate characteristic common to humanity, is eager for narratives. The compositions are essentially spatial, but it is almost inevitable to imagine significance – as of the encounter between a black young woman and an old white lady: they are just standing in front of one another as the viewers, in real time, are writing some sort of story for them. Distances, levels, speeds, expressions; the theatricality of Multitud meets some unavoidable performative reception as the pure presence of performers, perpassed by all sorts of readings coming from themselves and their bodies, generates layers of meanings as they are watched within the context of a work of art.

Multitud also operates in transforming not only how to look at bodies in movement but to reflect upon what is a body; alone, collectively, building relations: a body-multitude, a body-one, some-body. The moving images presented by the composition can be seen in a linear way, as if the trajectory of the work follows some idea of progress and dehumanization, but it seems richer to look at it not as it is about going from point A to point B. To perceive the spatial-time continuum as a spiral, as proposes Leda Maria Martins, allows one to perceive Multitud as a chaotic framework of multiple configurations possible to be brought into existence throughout collectivity.

So, the “merry-go-round” described in the synopsis of the show can be read as the potential for a multitude to create a hurricane by themselves but also, as followed by histrionic laughter, as the humanity being flushed down a toilet. Crawling over other bodies can be a symbiotic possibility, but one can see the traces through the path, the left-behinds. To fall can mean to be held. And the dream of collectiveness can also be turned into violent nightmares.

The crowd becomes a rabble. An angry mob makes it clear to see how power dynamics operate both individually and collectively. Multitud goes into a profoundly violent scene, where the aggressions of 99 against one echoes the reality in a hurtful way: lynching and attempts of lynching goes back hundreds of years and are still very present in everyday news of many places around the world. Back in 2014, in Rio de Janeiro (Brasil) a 14-year-old black teenager had his clothes ripped off, was spanked and locked to a post with a U-lock on his neck after being accused of a robbery attempt. The self-entitlement of a collectivity can be a beautiful utopia but is also especially dangerous.

Multitud starts with order and falling, flowing towards chaos and being held. It chooses not to end itself on violence, nor in laughter. Not even in taking care and being taken care of, but in an idea of constructing oneness. As if there is something yet to be found; something that can only be discovered through collective experience, through trial and error: echoing Beckett, “try again, fail again, fail better“. To allow for each multitude – that emerges, composes themselves and can later disappear – to find what it means to be together. Oneness, togetherness, whatsoeverness.

Sua critica nos leva ao interior do espetáculo, nos torna partícipes. Que lindo!