a radical exercise of imagination

amilton de azevedo writes about Carte noire nommée désir, by Rébecca Chaillon (France), presented in the 2024 Festival TransAmériques (FTA – Tiohtià:ké/Montreal). this text is part of a special coverage; the critic traveled to Canada at the invitation of the FTA.

“A long poem of creation tells us that, at some point, Exu was challenged to choose, between two calabash shells, which one he would take to a trip to the market. One contained good, the other contained evil. One was medicine, the other was poison. One was body, the other was spirit. One was what is seen, the other was what couldn’t. One was word, the other was what would never be said. Exu asks for a third calabash shell. He opened the three and mixed up the powder of the first two into the third. Shook well. Since this day, medicine can be poison and poison can heal, the good can be evil, the soul can be the body, the visible can be the invisible and what is not seen might be present. The spoken might not say anything and the silence can make vigorous speeches. The third calabash shell is of the unexpected: there lies culture.” [Luiz Antonio Simas in O corpo encantado das ruas (The enchanted body of the streets), on free translation]

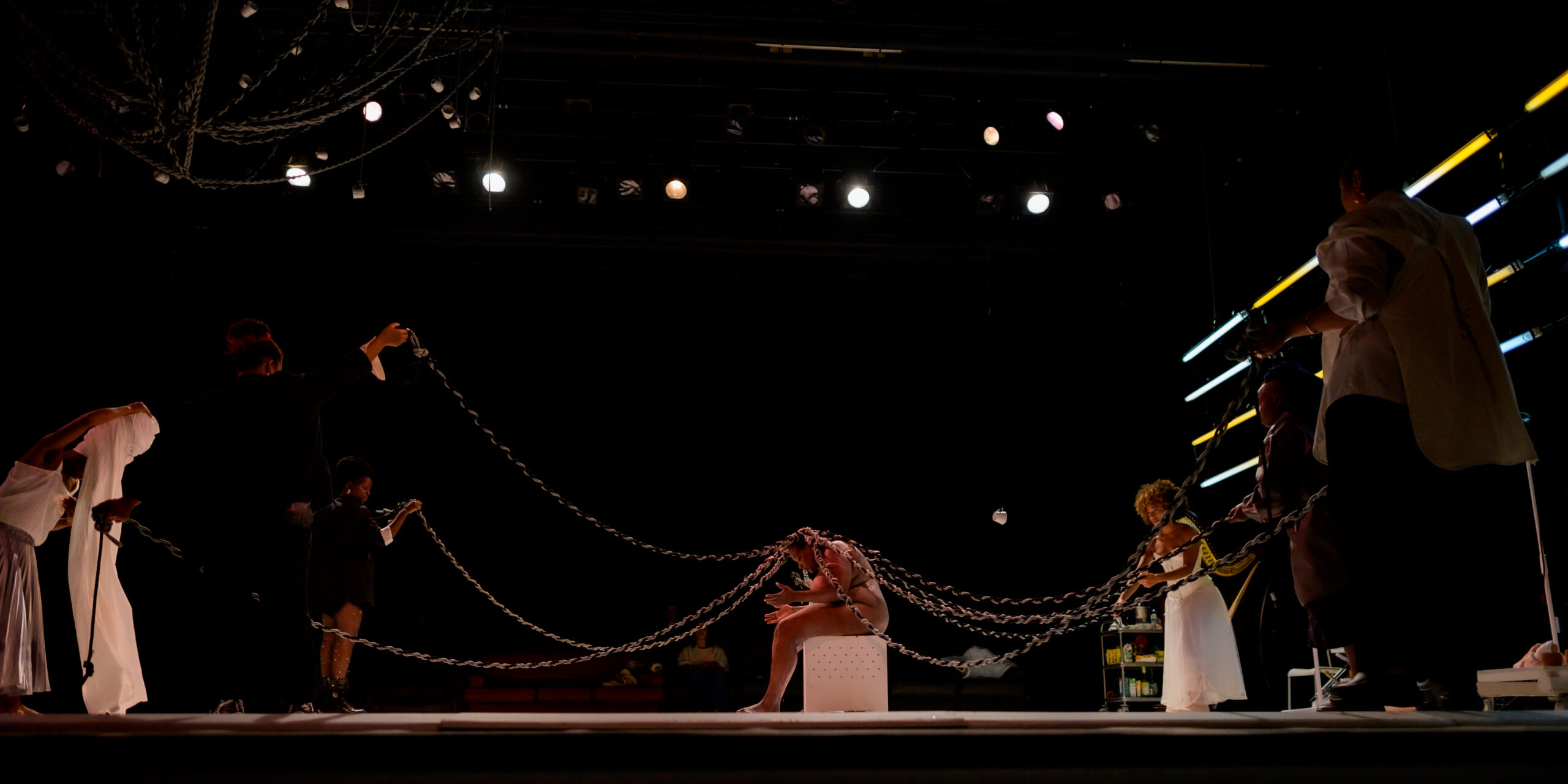

To braid: an ancestral communal technology from Africa that involves intricate geometry, collective sociability and empowerment. Also known for its appropriation worldwide and its use without acknowledging nor respecting its origin. Carte noire nommée désir (France, 2021) is the slogan for a french coffee brand of the 1980’s and Rébecca Chaillon’s outstanding attempt to turn not only the stage but the whole theatrical experience into an acid experiment on intertwining cultures. Two black ropes and a white one: the racial entanglement proposed by the performance announces itself on its materiality, dramaturgy and mise-en-scène.

If mixing up races can – and are – criticized within a historiographical perspective, Carte noire nommée désir proposes a “new” way of bonding. Throughout humor, cynicism and a light-hearted relation consolidated between performers and both audiences – separate, but equal, yet from a antagonistic Jim Crow perspective – Chaillon’s work is able to truly, and even dangerously, integrate throughout a provocative apparatus that effectively produces complicity, reflection and both loose and nervous laughter. Desire, representations, tropes, stereotypes, racism, violence, fetishism, sociability: eight black women inhabit a whole world within the 160 minutes of the piece transiting between different artistic languages and orchestrating its own complexity by flowing through the scene’s atmospheres.

- Read more: access this link for more theater critics written in english

- Read more: follow ruína acesa’s FTA special coverage

Carte noire nommée désir investigates the constitution of Blackness, especially by the lenses of becoming a black woman, and its satirical force relies mostly on imploding Whiteness’ production and projection of a racial hierarchy. In many senses, the performance reverberates the antimodern perspective of Denise Ferreira da Silva on “difference without separability“, the “cognitive plantation” idea from Jota Mombaça and crossing through Frantz Fanon’s research in “Black Skins, White Masks” and the effects of colonization on black subjectiveness. But it is not a work of art presented as a thesis: Carte noire mise-en-scène is a dynamic, provocative and vivid performance.

The insistence on evoking historical and popular culture tropes not only through irony and jokes, but in the compositions themselves, from the costumes to the narratives, can make both white and black audience feels uncomfortable while watching – reactions must be really different depending on the public and the place that the piece is being presented; in Avignon, Fatou Siby had her arm twisted by a man in the audience, the cast was physically assaulted and were called “dictators”.

Carte noire nommée désir is also about vulnerability – in the many senses that the word can abide. The performance dwells into the contradictions inherent to humanity, not evading that complexity at any moment and never organizing itself in a way that they could be seen as the owners of the truth, or the carriers of certainties. Its fragments are constantly reshaping the reception whilst their intention seems crystal clear. Carte noire is not pamphleteer theater, being profoundly dialect in its entirety. There is always a little noise in the images produced, as if the text is to remain open and fulfilled by each audience member’s imagination, background, experiences and worldviews.

And through the use of stereotypes and tropes, Carte noire makes them allies, not enemies, towards their implosion and the emergence of different or new ways of socializing and living with one another, recognizing difference as a basis for sociability but rejecting the colonial assumption of hierarchy. In “A Director Prepares“, Anne Bogart writes:

“When approaching stereotype as an ally, you do not embrace a stereotype in order to hold it rigid; rather, you burn through it, undefining it and allowing human experience to perform its alchemy. You meet one another in an arena of potential transcendence of customary definitions. You awaken opposition and disagreement.”

Burn through it: take them to the limit and see what it becomes; the alchemy is uncertain, as life, and what will be produced before one’s eye can be different to another. Right at the beginning, while the public enters the room, two performers are on stage. One is cleaning, the other is making ceramic cups. The cleaner uses bleach and seems bleached, and one can see her as a zombie, for her totally white eye lenses, but the white tainted mouth in her face can be a reference to the blackface practice, but the whiteness of her clothes and arms can be a satire towards building a whiteface. While she cleans, droplets of what looks like clay from suspended objects make the bright white floor dirty again, but also taints her costumes brown. When she finishes, a bucket of water filled with such dirt is splashed onto her. After this somewhat ritualistic cleansing, the other performers join in to collectively braid her hair with gigantic ropes and the all-so-white stage hosts a beautiful and slow-paced scene on what can be seen as the becoming and empowering of a black woman.

The atmosphere of Carte noire nommée désir is on constant and instantaneous shifting through the bodies, voices and actions of the cast. Racism and its ways of manifesting itself, from structural to recreational, passing through its social and subjective effects, are exposed in direct and indirect ways during the piece, and images can be perceived as violent and humorous from different points of view. Sometimes, the laughter of the audience could be seen as more unbearable and uncomfortable than what was happening on the stage.

During the charades scene in the May 26 presentation within the Festival TransAmériques (Montreal/Canada), the most interactive part of the piece, there was this one moment that heard no guesses from the audience. The answer provided by the performer works as sort of a twisting point, where the white people watching may realize that everything being shown is, perhaps, not so funny. Of course, the attitude of the cast and the intention of the scene are working precisely to such effect. The laughter followed by the discomfort of laughing.

Carte noire nommée désir does not addresses Whiteness aggressively. For it is more about them. An invitation to rethink crystalized and stalled worldviews; to implode racism, misogyny, objectification and fetishism within oneself as the audience is entangled by their dreams of oceans and desires of life. Beyond the satyre, the irony, the denouncement, what is experienced is the possibility of a radical exercise of imagination.

suas reflexões são um convite a criar na imaginação um mínimo, que seja, pedaço dessa performance tão desafiadora.